- Home

- C. Joseph Greaves

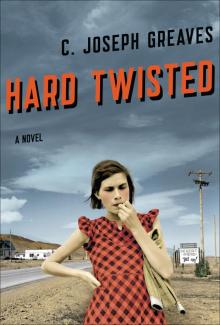

Hard Twisted

Hard Twisted Read online

This book is for my parents, Charles Alan Greaves and Jane Anne Greaves.

Contents

PART ONE

Chapter One: A Rooster Ain’t No Job

Chapter Two: Them All’s the Rules

Chapter Three: Damn Fools And Soldiers

Chapter Four: You Might Run by Him

PART TWO

Chapter Five: West of Here

Chapter Six: Something About a Horse

Chapter Seven: It Ain’t Even America

Chapter Eight: A Bigger Fire Than This

PART THREE

Chapter Nine: Hard Twisted

Chapter Ten: As Long as It Ain’t Here

Chapter Eleven: Put Not Your Trust in Princes

Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

Epilogue

A Note on the Author

Dearly beloved, we are God’s children now; what we shall later be has not yet come to light.

—I JOHN 3:2

PART ONE

Chapter One

A ROOSTER AIN’T NO JOB

THE COURT: Back on the record in Case No. 7421/6150. All jurors are present and the defendant is present. Mr. Pharr?

BY MR. PHARR: Thank you, Your Honor. The People call Lottie Lucile Garrett.

(THE WITNESS, LUCILE GARRETT, IS DULY SWORN.)

BY MR. PHARR: Now, Miss Garrett, you understand that you’re under oath, do you not?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: And therefore required to tell the truth?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Now then, would you please tell the gentlemen of the jury how it was that you first came to meet Clint Palmer?

A: Well, we was camped out on the Gay Road—

BY MR. HARTWELL: Objection, Your Honor. At this time we would renew our motion regarding the testimony of this witness.

THE COURT: All right. I suppose there’s no avoiding this. Henry?

BY MR. PHARR: Miss Garrett, were you ever married to the accused?

BY MR. HARTWELL: Objection. Calls for a conclusion. Lay opinion also.

THE COURT: Overruled. You may answer.

A: No, sir. I ain’t never been married to nobody.

(PROCEEDINGS INTERRUPTED.)

THE COURT: Order. We’ll have none of this. One more outburst and I’ll clear the courtroom. Henry?

BY MR. PHARR: You never went through any kind of wedding ceremony with the accused?

A: No, sir.

Q: He never gave you a ring?

A: No, sir.

Q: You never stood up before a preacher?

A: Never did. Never would, neither.

(PROCEEDINGS INTERRUPTED.)

THE COURT: Order. Do not test me.

BY MR. PHARR: Submitted, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Very well. Does counsel wish to voir dire?

BY MR. HARTWELL: Thank you, Your Honor. Isn’t it true that you and Mr. Palmer cohabited together over a period of several months during the years 1934 and 1935?

A: Did what?

Q: Cohabited. Lived under the same roof.

A: Well. There weren’t no roof to speak of.

(PROCEEDINGS INTERRUPTED.)

THE COURT: Order. Not another peep, I warn you. And the witness will answer counsel’s questions without gratuitous exposition.

BY MR. HARTWELL: You lived together as man and wife.

BY MR. PHARR: Objection.

THE COURT: Sustained.

BY MR. HARTWELL: You shared a bed? Or a bedroll?

A: It weren’t never my idea.

Q: But isn’t it true that you held yourselves out to the public as man and wife?

A: That’s a lie. I never done no such thing.

Q: In Monticello, state of Utah, on December the thirty-first of 1934—

BY MR. PHARR: Objection. This is too much, Your Honor. I would remind the court—

THE COURT: All right, all right. That’s enough, both of you. I can see where this is heading. The defense motion is denied.

BY MR. HARTWELL: But, Your Honor—

THE COURT: For Christ sake, L.D., these men got crops planted. I said motion denied.

BY MR. HARTWELL: Exception.

THE COURT: Noted. Henry, you may proceed.

BY MR. PHARR: Thank you, Your Honor. Miss Garrett, I think we were by the side of a road somewhere.

They followed the Frisco tracks with their bodies bent and hooded, the pebbling wind audible on the back of her father’s old mackinaw. To the west, a line of T-poles stretched to a dim infinity before a setting sun that melted and bled and blended its sanguinary light with the red dirt and with the red dust that rose up like hell’s flame in towering streaks and whorls to forge together earth and sky.

Great deal on land! her father called over his shoulder. Bring your own jar!

They came out to the highway and paused there before turning west, the windblown dust in spectral fingers reaching across the blacktop before them. First one car passed without stopping, then another.

You gettin hungry?

No, sir.

The next vehicle that passed was a slat-sided Ford truck that slowed and shimmied and veered crazily onto the shoulder, and as they hurried to meet it, she saw through the swirling grit the crates of pinewood and twist-wire stacked beneath its flapping canvas tarpaulin.

Her father worked the latches and lowered the endgate and vaulted into the truckbed. She reached a blind hand for him and felt herself rising, weightless in a grip as hard as knotted applewood, his mangled finger biting into the soft flesh of her wrist.

A bonging sound on the cab roof riled the chickens, and a voice called out from the lowered window, Get on up front, you dumb Okies!

The man looked across her lap and studied her father’s shoes. He said his name was Palmer, and that he was a Texan, and a cowboy. He wore sharp sideburns and a clean Resistol hat cocked forward over pallid eyes gone violet in the fading glow of sunset, and she could see that he was small—perhaps no taller than she—and that something fiercely defiant, something feral, was in his smallness.

You get a gander at them gamecocks? the man asked without taking his eyes from the roadway.

Look like right fine birds, her father allowed.

The man chuckled. Mister, them’s the gamest fightin roosters this side of the Red, for your information.

That a fact.

Damn right that’s a fact. The man nodded once. Damn right it is. You know fightin birds?

Her father did not respond, and the man leaned forward to study his profile before dropping his eyes first to her sweater and then to her lap, returning at last and again to her father’s shoes.

How long you been outside, cousin?

How’s that?

The stranger’s smile was sudden, and unnaturally brilliant, and hot on the side of her neck.

So that’s how it is.

Do I know you? her father asked, leaning now to face the man.

Maybe you do and maybe you don’t, the man said, his ghost reflection grinning in the darkened windscreen. But I surely do know you.

They’d built a fire in the lee of the ruined house, and her father squatted before it stirring red flannel hash with a spoon. The temperature had dropped with the sun and she wore his mackinaw now like a mantle while he sat his heels and rubbed his hands and warmed them over the skillet, the tumbled walls around them shifting and changing, moving inward and then outward again as though breathing in the soft orange glow like a living thing.

Embers popped, running and skittering with the wind. To the north she saw other fires speckling the void, and she studied their positions as an astronomer might chart the nighttime heavens.

More to night, she said.

Her father followed her gaze. These is hard times, honey

. Ain’t nobody hirin. Least not in Hugo, anyways. I was thinkin I might light a shuck for Durant come sunrise. Man said a mill there was lookin for hands. Miz Upchurch could mind you for a day.

I don’t need no mindin.

He paused and studied her burnished profile, her cheek and lashes luminous in the fireglow.

Tell you what then. You can mind Miz Upchurch. Haul her water and such. You tell her I’ll be back by nightfall.

She wielded a broken twig, tracing random patterns in the dirt. Somewhere beyond the firelight, a car passed on the highway.

Who was that man?

Just a man.

He said he knowed you.

He didn’t mean like that. More like my kind is what he meant.

What’s your kind?

Her father stirred the skillet, and paused, and stirred it again. He tapped the spoon on the iron rim.

Only the good Lord knows what’s in a man’s heart, Lottie. Happy is the man who follows not the counsel of the wicked nor walks in the way of sinners. He wiped his nose with his wrist. That there’s from Psalms.

She poked her stick into the fire and withdrew it and blew out the flame. Then she wrote a secret in the air, and studied it, and watched it disappear in the ravenous wind.

The sun was two fingers off the horizon by the time she awoke. The wind had stilled and the sky had hardened to a diamond blue the weight of which lay upon her in her blankets like some vast and shoreless ocean.

She turned, shielding her eyes with a hand. The white ash of a kindling fire warmed the coffeepot beside her father’s bedroll.

She sat up yawning, and then rose to gather some yellowed newsprint from their cache before heading to the creekbed. On her return to the campsite she bent and snapped an aloe spine, spreading the sticky unguent onto her blistered ankle the way the Choctaws did, then she tiptoed back to the fire. There she brushed her hair in long, measured strokes, staring out to the north where the night fires had been, but where nothing now stirred.

Among her father’s things she found his small leather Bible, and she sat in the shade of the broken house and read from Exodus about the command to the midwives until, setting the book aside, she closed her eyes and touched the slender cross at her throat, praying aloud, Dear Lord, first for her mother’s eternal soul, and then for her uncle Mack, and lastly for a Little Buttercup doll with the blue ruffle dress and the matching bonnet with genuine lace trim, her head bowed as she spoke the words, her voice a tin voice in the still and wilted air.

A vulture kited overhead, its shadow rippling darkly over the ground, over the house, over the day.

Over her life.

She replaced the book and stood and stretched again before walking into the sunlight, where she shook the grit from her socks and boots and pulled them on and walked a tentative circle. Then she sat and removed the one boot, folding a strip of newsprint into her sock and replacing the boot and walking another circle.

She hadn’t gone but a hundred yards toward the Upchurch farm when she caught sight of the truck. It was parked beside the highway, and the man was standing behind it like an exclamation point after a shouted command.

She looked to the farmhouse, small yet on the horizon, and back again to the truck.

He was leaning on the fender, the heel of one boot resting in the crook of the other. The sun was to his back, and his hat flapped listlessly against his thigh. He followed her approach until she’d reached the edge of the bar ditch, where she stopped and studied with lowered eyes whatever grew within.

What’s the matter, I’m too ugly to look at?

You ain’t ugly.

The man worked a matchstick in the corner of his smile.

If you’re lookin for my pa, you’re too late. He’s over to Durant. That’s his bad luck then, ain’t it. Here I come all this way to offer him a job.

What job?

He gestured toward the truckbed. Brought him a rooster.

A rooster ain’t no job.

He shook his head sadly, grinning into his hat crown.

What all’s he supposed to do with it then?

Hey, you remind me of someone, do you know that? Was you ever in the movin pictures?

Not hardly.

Then it was one of them photo magazines. Am I right?

She lowered her gaze, the heat prickling her face.

What’s your name, anyways?

Lucile. Lottie to my friends.

His eyes left hers to scan the field behind her, settling on the spavined house and the broken windmill and the cold thread of woodsmoke hanging above them.

I got friends.

How old are you, anyways? Fourteen?

Thirteen.

Thirteen. He nodded once. I got me a niece name of Johnny Rae, and she’s just about your age. She’s my sister’s youngest.

Lottie shaded her eyes. Does she live in these parts?

He nodded again. Matter of fact, she and me, we was gonna take us a drive down to Peerless tomorrow to visit my daddy. You ever been to Texas?

I don’t know.

My daddy’s got him a farm down there with cows and goats and pony horses. It’s too bad you all couldn’t come with us, cuz them horses need to get worked. He looked south, far beyond the horizon. Could use us another hand tomorrow, that’s for damn sure.

She studied the stranger’s profile. His tooled boots and his new Levi’s and his polished oval belt buckle.

My pa wouldn’t let me go noways.

How come? Why, you and me and Johnny Rae and her mama, we all could have us a day. Maybe eat us a picnic dinner. You like fried chicken?

I suppose.

And they’s a swimmin hole for you girls if the weather holds. Hell, we all’d be back by sunset.

Well.

You want I should talk to your pa?

She shrugged. I don’t know.

What’s your pa’s name, anyways?

Dillard Garrett.

Dillard Garrett, he said. As if weighing it.

They faced each other in the silence that followed, his cornflower eyes locked on to hers. She looked away, fists thrust into pockets.

I got to go.

You need a ride somewheres?

No, sir.

Don’t sir me. I ain’t your daddy.

All right.

Clinton Palmer. That’s my name. Clint to my friends.

Now you’re funnin me.

Grinning again, he removed the matchstick and slid himself upright.

Tell you what. Come over here and take this rooster for your pa. I’ll come by in the mornin, and him and me’ll have us a little talk.

He climbed into the truckbed and, without bending, slid the lone crate toward the endgate with his boot.

Careful now. That’s one rank bird.

The cock was rust over black, and the black of it held a greenish cast in the gridded sunlight. It fanned its ruff and pecked at the wire where she reached her hand.

Does he got a name?

No, ma’am, but I reckon you could give him one.

She tipped the crate carefully with her forearm, hiking it onto her hip. The bird was all but weightless, its pink talons balled and its pink head rooting in short and halting jerks.

He sure is fancy, but he don’t weigh nothin a’tall.

She carried the crate across the ditch and hiked it again as she walked, pausing but once to turn and face the slender figure still skylighted in the truckbed.

I got me a notion to name him Clint.

The mill jobs in Durant had been but two jobs, for which over a hundred men had applied. Her father’s voice quavered as he told the story, and between long tugs of bonded whiskey he cursed the day and he cursed the mill foreman and he cursed Mr. and Mrs. Roosevelt for good measure.

The rooster stirred in its cage.

It’s got to where a white man can’t find a honest day’s work for a honest day’s wages, he rasped, his hands trembling, his dark eyes shining in the firelight. It’s

got to where a Christian man is treated no better than a godless goddamn nigger.

Lottie listened, chewing and nodding in mute commiseration, waiting until at last her father had stoppered the bottle and rolled a smoke and leaned back into his bedroll. Only then did she broach the subject of Peerless, but his answer was curt, and emphatic, and so she let the matter drop.

The truck sat shimmering in the roadside sun as Lottie emerged barefoot from the creekbed. Before it were two figures in backlight, one tall and one short, the shape that was her father listening with folded arms while the smaller man spoke and gestured, first to the truck and then to the highway, and then in a sweeping arc that encompassed the broken house and the field where Lottie crouched in the pokeweed, her eyes closed, her lips moving in swift and silent prayer.

Where’s Johnny Rae?

Lottie paused with her foot on the running board as Palmer held the door.

Packin her kit bag, I reckon. We’ll fetch her up in Hugo.

He closed the door and circled the truck, clapping dust from his hands, his eyes scanning the highway in both directions.

The cab where she waited was spare and tidy and bore the masculine smells of motor oil and leather and old cigarettes. A spider crack stippled the corner of the windscreen. A cowhide valise, like a doctor’s bag, rested on the seat beside her.

Palmer clambered in and slammed the door, setting his hat atop the valise and raking his hair with a hand. He looked at her and smiled. He turned the ignition and pressed the starter and mashed the pedals, working the shift lever up and back until the gears ground and caught and the truck lurched forward, rocking and wheeling southbound onto the empty highway.

That weren’t too difficult.

What all’d you tell him?

Oh, let’s see. That I was Clyde Barrow and needin me a gun moll, and that we all was gonna rob us some banks and shoot our way down to Mexico.

She giggled. You’re crazy.

He said to bring him one of them sombrero hats is all.

The day was warm, and the warmth of it rippled on the scrolling blacktop. She watched him in stolen glances; the line of his nose and the set of his jaw and the dance of his hair in the breeze.

What is it?

Nothin, she replied.

You was smilin at somethin.

Hard Twisted

Hard Twisted