- Home

- C. Joseph Greaves

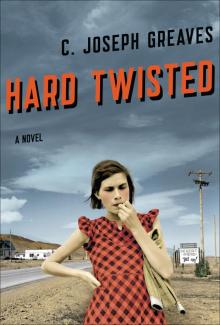

Hard Twisted Page 2

Hard Twisted Read online

Page 2

It weren’t nothin to talk about.

They passed beanfields and cornfields and grazing cattle, and then the ironworks and the cotton compress, slowing only at the stockyard where the roadway and the rail line crossed. Palmer pointed out the railmen’s barracks, and the ice plant, and a gated cemetery where he swore that elephants and circus clowns had been buried.

A redbrick bank was on the main street, and a general store, and they passed them both before turning left at midblock down a narrow alley.

Wait here a minute, Palmer said, setting the brake and collecting his hat and sliding from under the wheel.

She sat and watched as cars and trucks and occasional horses plodded past the alley mouth like targets in a carnival shooting gallery. She fingered the knobs on the dashboard. She hummed. When a man approached the truck and removed his hat to ask if she could spare a dime, she told the man that she had no dime to spare.

When Palmer returned, he was swinging a brown paper sack that he tucked between his legs as he resumed his place at the wheel.

Change in plans, he announced breezily, releasing the brake and reversing the gears and slinging his arm over the seatback. Looks like Johnny Rae and her mama done already left. We’ll have to meet ’em down there, if that’s okay with you?

I guess.

He turned to her and winked. Bigger shares for you and me if we hit us a bank on the way.

They passed the Methodist church and the Baptist church, and outside of town they passed the tie-treating plant, where Lottie pinched her nose against the treacle smell of creosote. Beyond these, the countryside opened and the highway rose and fell and she saw in the rising a jagged suture of brighter green that ran for miles from east to west and marked the Red River valley.

They crossed into Texas on the Highway 39 bridge at Arthur City, where she watched their reflection warp and disjoin and form again in the storefront glass. They turned onto a gravel side road, recrossing the railroad tracks and dropping into the cool and empty shade of the riverbank.

You need to pee? he asked, setting the hand brake.

I don’t know.

If you don’t know, who does then?

He killed the engine and shouldered his door, slipping the paper sack into his seat pocket as he alighted. She watched as he walked into the rushes and curtsied and fumbled with his trouser front. Then he crossed the little clearing to a downed log and settled himself in the shade, fanning his face with the hat.

You all comin out? he called to the truck, and she opened her door and closed it and moved through the dappling sunlight and the pustular smell of rotting bulrush.

You gettin hungry?

A little.

He shifted where he sat. They’s a café in Paris. That’s about a half hour’s drive from here. Think you can hold out?

I guess.

As she settled on the log beside him, he placed the cowboy hat on her head and leaned back to study the effect. He reached for the sack, folded back the paper, and uncorked the bottle within with his teeth. He took a long drink of the amber liquid and offered the bottle to her.

You sure? ... All right then, suit yourself.

He set the bottle on the ground, crossing his legs and prying his boots off each in turn. He wore no socks and his feet were as a child’s feet, small and veined and pale as candle wax.

I got me a notion to wash up, if that’s all right with you. Cleanliness bein next to godliness and all.

He stood and unsnapped his shirt, draping it on a low branch. He was lean and hard-muscled, tanned on his neck and forearms, and he smiled at her over his shoulder as he sauntered through the canebrake. At the river’s edge he stopped to roll his pantlegs before wading into the water.

She watched him closely, pretending she was not. Watched as he produced a kerchief from his pocket. Watched as he dipped the cloth and wrung it, half-squatting, scrubbing at his face and neck. Watched as he turned to where she sat, his voice echoing across the wide and silent river.

Come on, Bonnie Parker! A little water won’t kill you!

She looked from the man to the bottle and back again to the man. To the truck, like a great wounded beetle with its one door open. To the shirt, limp and empty as a snakeskin.

At the river’s edge the air was warm and alive with insects seen and unseen, and she watched the threaded grasses streaming in the water beyond the wide shadow of her hat brim. Palmer stood in full sun, hands on hips, the cold water glistening on his chest.

Come on in. It ain’t that fast.

She waded out to where he stood, the cold mud oozing between her toes, stepping and pausing, stepping and pausing, her weight braced against the heavy current, while upriver, before the riveted railroad bridge, sunlight danced on the water.

He lifted a hand to her cheek, rubbing a spot there with his thumb, his hand lingering on her face and on her neck as though gentling a skittish yearling. Then he slapped the bandanna across his shoulder, reaching his hands to her shirtfront.

What’re you doin?

Just hold still a second.

Quit it!

She twisted away, backing and almost falling.

Hey! Careful of that hat!

She stood with her legs braced, her fear and her excitement veiled by the shadow of the hat brim.

I was only tryin to help. It was kindly gettin close in that truck, if you get my meanin.

Her face burned. She looked to her feet, or to where her knees below the rolled pant cuffs met the sheeting water.

What’s the matter now?

She shrugged. I’m cold.

Here.

She accepted the cloth, and after he’d waded past her toward the bank, she bent and submerged it in the river, raising it to her nape, shivering as the water ran in hard, icy fingers down her shirtback.

I’ll be over yonder with my eyes closed! his voice faded behind her. Don’t you worry about me!

She lifted her sweater and her shirttail, scrubbing at her underarms. She swirled the bandanna and wrung it out and sniffed of it and swirled it again.

Hey! You ain’t drowned out there I hope!

She could not see him, but when she’d waded ashore, she found him fully dressed and reclined against a treetrunk with his hands nesting the bottle in his lap.

How was that?

She shrugged.

He rose, brushing at his seat and accepting the wet cloth and retrieving the hat from her head.

I don’t know about you, he said, but I could eat a folded tarp.

Back inside the truck cab, he uncorked the bottle and took another drink.

Here.

No thanks.

Go ahead. I won’t tell your daddy.

That’s all right.

You ain’t scared, are you?

She looked at him, and at the bottle. She accepted it, sniffing at the neck and crinkling her nose.

Go on, it won’t kill you.

I know it. She looked at him again and closed her eyes and drank.

A spray of bourbon whiskey wet the windscreen. At this Palmer roared, rocking and red-faced, his child’s feet stamping the floorboards.

Whoooeee!

’Tain’t funny, she gagged, coughing into her sleeve.

Tell you what though, it’ll do till funny comes along. Give that here.

He drank again and wiped his mouth on his shirtsleeve. And as he nestled the stoppered bottle inside the valise, she saw through still-watering eyes the hard, blue shape of the pistol.

They sat as bookends in a booth by the window. Fly husks on the faded sill were hard and iridescent in the sunlight, and Lottie watched them and their faint reflections rocking in unison to the slow wash of the ceiling fan. A waitress, herself nearly as desiccated, filled their mugs and produced napkins and flatware from a sagging apron pocket.

They’s a children’s menu on the back, she said.

Palmer ignored her, intent on the streetscape. There were more and newer cars than in Hugo, and fewer hor

ses. On the corner opposite the café, a Negro boy yoked in a wooden sandwich board held a newspaper aloft to the passing cars. The headline read MORE RELIEF FOR FARMERS.

Palmer opened his menu, and Lottie did likewise. There were breakfast plates and lunch plates and blue plate specials.

What all can I have?

Whatever you want, sweetheart.

The waitress returned with a pad, and she dug a pencil from behind her ear as Palmer ordered the chicken-fried steak with biscuits and gravy and pinto beans.

Lottie bit her lip, twisting and untwisting the same lock of hair. She ordered pancakes with bacon, and fried chicken with green beans, and hot apple pie with a slice of cheddar cheese.

Expectin company? the woman snorted, jotting the order with eyebrows raised.

Palmer turned to follow her receding back before reaching into his valise and tipping the bottle into his coffee. He stirred it and tinked at the rim and raised the mug as if to Lottie’s health.

How much further to Peerless?

He sipped. Thirty or forty miles.

How long will that take?

Maybe a hour, maybe more.

You reckon they’s worried about us?

You ask a lot of questions, do you know that?

That’s what my daddy says. He says I’m like the queen of Sheba, right there in first Kings.

He set down his cup and leaned forward and thumbed back his hat. Listen, sister. If I wanted a sky pilot for company, I’d of stopped at one of them churches and waved me a dollar bill.

What do you mean?

I mean not everbody was raised up on dried prunes and proverbs.

Don’t you never read the good book?

The good book. What’s it say in that book of yours about farmers gettin run off their land? What’s it say about Jew bankers takin food money from widows and orphans?

Her face was a blank.

You think they’s anybody in them churches gives a rat’s ass whether you eat or starve? Well, let me tell you somethin I learnt a long time ago, and that’s this right here. You want anything in this life, you got to go on out and grab it. You just do what you gotta do, and don’t go askin no permission or beggin no forgiveness. And for Pete sake, don’t go all the time askin the good Lord for help, cuz if you want my view on the matter, he’s done got quit of the helpin business.

She blinked.

You got a problem with that, you let me know right now, and I’ll give you a ride straight back to your daddy.

I didn’t say nothin.

Okay then.

He leaned back in his seat. He returned his attention to the window, where the newsboy’s sign lay jackknifed on the sidewalk, the boy himself gone as though vanished in some heavenly rapture peculiar to his race.

Lottie took up her knife and tilted it, examining her reflection in the blade. Palmer watched her with a sidelong glance as the light bar played on her face.

Try that spoon there. You’ll be all topsy-turvy.

She set down the knife and took up the spoon, holding it out like a mirror.

Tell me somethin. How long you been hoboin with your pa?

She shrugged. I don’t know. Two years.

What about before that?

Before that I lived with Uncle Mack, up to Wilburton.

Uncle Mack.

She nodded. Tilting her head, examining the upside-down girl.

What all happened to him?

I don’t know. Got tired of havin me, I guess.

So where’s your mama, anyways?

Dead.

Well, shit, there you go. My mama too. Maybe that’s how come I knowed right away that you and me was gonna become special friends.

The waitress appeared beside them with heavy plates two to a hand.

More coffee comin, she said, tearing a sheet from her pad and slapping it down at Palmer’s elbow.

Lottie ate the pancakes, and the chicken, and they nudged the pie plate back and forth between them. They ate mostly in silence, watching the cars pass on the street, and when she would glance at him and their eyes would meet, she would giggle and cover her mouth with a hand.

When they’d finished eating, Palmer peeled back the check and studied it and told her to go outside and wait in the truck.

She sat with the window rolled watching the fountain in the town square until Palmer appeared from the alley side of the building, hurrying to the truck and climbing in after his valise. He fumbled with the key and jabbed at the starter, grinding the gears and lurching them into traffic as cars swerved and horns sounded. They turned right at the first corner and left at the next, with Palmer all the while watching behind them in the mirror.

In late afternoon they quit the highway for the county road. They passed through miles of wooded fields and blackland farms before swinging onto a gravel track by a cemetery, where a small dog shot through the iron gates and heeled them for almost a mile.

The track then narrowed and darkened as shade trees crowded their passage. They rounded another curve and Palmer braked the truck and tilted his hat, leaning out the window to hawk and spit through their settling dust cloud.

There she is.

Lottie sat up to look. Through a gap in the tree line she made out a long field sloping away to a swaybacked barn. Beyond the barn was a peeling clapboard house flanked by shade trees, one living and one dead, and beyond the trees was a pasture, this with an empty stockpond in which two rawboned horses posed with their heads low and their tails swaying and switching.

Another tree line marked the far boundary of the pasture. She saw no cattle or goats and no pony horses, and she could imagine no swimming hole on the land or in the jagged cut that ran beyond it.

Okay then. Here we go.

He climbed down to free the rusted loopwire that held the sagging gate upright. The horses lifted their heads as he returned to the truck and slammed the door and drove it forward and alighted again to close the gate behind them.

They parked in the shade of the barn. Swallows flew at the sound of their slamming car doors. Somewhere in the distance, chickens gabbled and clucked. Palmer turned to the house, cupping his mouth with his hands.

Hello! Anybody home?

All was silence.

The barn before them listed precariously. One stall housed a rusted jalopy blinded by missing headlamps; the other, an ancient two-furrow horseplow. Littering the ground and lining the open-stud walls were sacks and barrels, tin cans and fruit jars, and rusting tools of every description. Against the back wall, spotlighted by a gap in the high tin roof, stood a tumbledown tower of hay.

I got to pee bad.

Privy’s around back. I’ll go on inside.

The outhouse was rank, and so she squatted in the bare dirt behind it. The sun was high and the air warm and still, and the stillness of it hummed in her ears. She listened for the distant sound of voices raised in greeting, but she heard nothing.

The porch sagged where the paint had worn, and her bootheels rang hollow on the steps. She opened the screen door and paused, and there spied Palmer’s back framed in an open doorway where he knelt before a woodstove. He pivoted at the sound of the doorspring.

Come on in. Looks like we missed ’em.

The house was cool despite the sun. A small front parlor was sparsely furnished with a cracked leather sofa and a matching wing chair, its brass rivets missing. Lace hung limply over milky windows. Beyond this room was the kitchen, and beyond the kitchen a narrow hallway that ran darkly toward the back.

Where all’d they go?

They’s a note, he said without turning.

It lay on the kitchen table beside the valise; grease pencil scrawl on a flattened paper sack.

Clint—Could not wait no longer. Rode out with girls to river. Will camp for the nite. Make yorself to home. H.P.

She stared at the scribbled words until the words vibrated and blurred and she felt a hot streak on her cheek. At this the vague shape of him rose from the stove an

d crossed to where she stood, and she felt his strong hands on her shoulders.

Come on, Bonnie Parker. Don’t go bawlin now. It ain’t the end of the world. We can ride with ’em some other time, and that’s a promise. Meanwhile, we got the place all to ourselves, and we can have us a swell time. Come on now.

She nodded, leaning away to look at him.

I’m sorry, she said, sniffling. I know it’s the Lord’s will.

The slap was swift and sharp, the force of it spinning her sideways into the table.

What did I tell you about that nonsense?

She raised a hand to her face. She opened her mouth to speak, but no words came. She turned and ran for the door.

He caught her in the front parlor and pulled her backward, kicking and squirming, and he wrestled her onto the sofa.

Hold on now. I said stop, dammit, and settle down.

His hands gripped her wrists, straitjacketing her in his lap.

I hate you!

You listen to me for one second. Just listen.

She struggled again, and then was still.

I done fed you, and I drove you all the way down here so’s you could have a little fun for yourself, and all I ast in return was one little thing. All I ast was for you to quit your mealymouthed holy-rollin for one goddamn day. Now is that so much? Huh? Is it?

He leaned and tried to turn her, but she wouldn’t turn.

Come on, Lucile. Where’s that other cheek I keep hearin about?

She tried to stand, and he hugged her tighter.

Let go!

Come on, darlin. This ain’t no way to be.

She looked away, turning her face to the door and the porch beyond. Don’t you never hit me again.

Don’t you never give me no cause again. How’s that for a square deal?

On the porch the angled sunlight quartered the floorplanks. Houseflies jumbled noisily beyond the screen.

All right.

All right then.

He released his grip, and she slid quietly from his lap.

I got to start us a fire. And then I got to feed and water them nags. Then we can play some dominoes or take us a little walk, all right?

She nodded.

Will you help me with them horses?

Can’t they be rid?

Well. These ones ain’t exactly saddle broke is the thing. Unless you’re some kinda buckaroo cowgirl and me not knowin it.

Hard Twisted

Hard Twisted